Anastasia (1956 film)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

| Anastasia | |

|---|---|

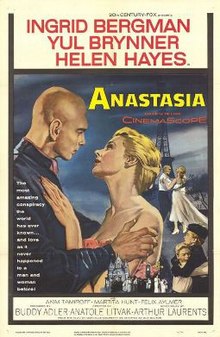

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Anatole Litvak |

| Screenplay by | Arthur Laurents |

| Based on | Anastasia (1952 play) by Marcelle Maurette |

| Produced by | Buddy Adler |

| Starring | Ingrid Bergman Yul Brynner Helen Hayes |

| Cinematography | Jack Hildyard |

| Edited by | Bert Bates |

| Music by | Alfred Newman |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Languages | English French |

| Budget | $3.52 million[1] |

| Box office | $4.3 million (US and Canada rentals)[2] |

Anastasia is a 1956 American period romantic drama film directed by Anatole Litvak and starring Ingrid Bergman, Yul Brynner and Helen Hayes. The screenplay written by Arthur Laurents is adapted from a 1952 play of the same title by French dramatist Marcelle Maurette, which is in turn inspired by the story of Anna Anderson, the best known of the many Anastasia impostors who emerged after the Imperial family were murdered in July 1918.[3]

Set in interwar France, the film follows a plot related to rumors that the Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia, the youngest daughter of the late Tsar Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, survived the execution of her family in 1918. Russian General Bounine (Brynner), former leader of the White Army during the Russian Revolution, along with his associates plot to swindle an inheritance of £10 million from the Grand Duchess using an amnesiac (Bergman) who looks remarkably like the missing Anastasia. The exiled émigrés of the Russian aristocracy, in particular the Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna (Hayes), must be convinced that their handpicked claimant is legitimate if the plotters are to get her money.

The film represented a Hollywood comeback for its star Ingrid Bergman, after several years working exclusively in Europe following her much-publicized affair with Roberto Rossellini.[3] She won the Academy Award for Best Actress, the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama, and the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress for her performance.

Plot

[edit]Though the last Russian Tsar and his family were executed in 1918, rumors persisted that his youngest daughter, the Grand Duchess Anastasia, somehow survived. In 1928 Paris, Anna Koreff, an ailing woman resembling Anastasia, is brought to the attention of former White Russian General Bounine, now the proprietor of a successful Russian-themed nightclub. Bounine knows that while Anna was in a mental asylum being treated for amnesia, she told a nun that she was Anastasia. When approached by Bounine and addressed as the grand duchess, she refuses to have anything to do with him. She flees and tries to throw herself into the River Seine, but is stopped.

Bounine meets with his associates Boris Chernov and Piotr Petrovin. Bounine has already repeatedly raised funds from stockholders (eager to gain a share of £10 million belonging to Anastasia held by an English bank) based on his claim that he had found Anastasia. Privately he admits it is a scam. But the stockholders have lost their patience and given him eight days to produce her.

Bounine arranges for Anna to be intensively trained to pass as Anastasia. During this time, she and Bounine begin to develop feelings for one another. Later, in a series of carefully arranged encounters with former familiars and members of the imperial court, Anna begins to display a confidence and style that astonish her skeptical interlocutors.

Anna has to go to Copenhagen, where she has to convince the highly skeptical dowager empress, Anastasia's grandmother, that she is Anastasia Romanov. Meanwhile, Bounine becomes increasingly jealous of the attentions that Prince Paul, another fortune hunter, pays to Anna. At a grand ball in Copenhagen at which Anna/Anastasia's engagement to Paul is to be announced, the dowager empress has a final private conversation with her. Although aware of Bounine's machinations, Empress Marie Feodorovna believes that Anna is truly her granddaughter. Realizing that Anna has fallen in love with Bounine, she helps her run away with him. The empress then makes it known to those around her that Anna is not Anastasia, although it is left ambiguous if she accepts that notion.

Cast

[edit]

Credits from the American Film Institute:[3]

- Ingrid Bergman as Anna Koreff / Anastasia

- Yul Brynner as General Bounine

- Helen Hayes as the Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna

- Akim Tamiroff as Boris Andreevich Chernov

- Martita Hunt as Baroness Elena von Livenbaum

- Felix Aylmer as Chamberlain

- Sacha Pitoëff as Piotr Ivanovich Petrovin

- Ivan Desny as Prince Paul von Haraldberg

- Natalie Schafer as Irina Lissemskaia

- Grégoire Gromoff as Stepan

- Karel Štěpánek as Mikhail Vlados

- Ina De La Haye as Marusia

- Katherine Kath as Maxime

- Eric Pohlmann as Von Drivnitz

- Olaf Pooley as Zhadanov

- Peter Sallis as Grischa

- Tamara Shayne as Zenia

- Nora Nicholson as Lady-in-Waiting

- George Pravda as Danish Customs Officer

Background

[edit]Historical basis

[edit]

The play and film are both inspired by the phenomenon of Anastasia impostors, who appeared in the years following the Russian Imperial Romanov family's death in July 1918.[3] Due to the disposal method of the remains and later Soviet government attempts to downplay the killings, claims of surviving Romanov family members would percolate for years to come. The location of Anastasia's remains would not be confirmed until 2007.

Anna Anderson (born: Franziska Schanzkowska) was arguably the best known of the Anastasia impersonators.[4] In February 1920 she was institutionalized in a Berlin mental hospital after a suicide attempt. She initially refused to identify herself, later going by "Anna Tchaikowsky". Over the next few years, the woman was identified by several White Russian émigrés as Anastasia. She lived with a succession of émigrés and exiled White Russian nobles, with varying degrees of belief or skepticism in her identity as Anastasia.[4] She eventually died in in the United States in 1984.

Literary and stage adaptation

[edit]Anderson's supposed identity was a popular sensation from the early-to-mid 1920s, with various books and pamphlets repeating her claims published throughout the years.[4]

Two such books, the pro-Anderson Harriet von Rathlef's Anastasia, ein Frauenschicksal als Spiegel der Weltkatastrophe (Anastasia, a Woman's Fate as Mirror of the World Catastrophe) and the anti-Anderson Pierre Gilliard and Constantin Savitch's La Fausse Anastasie (The False Anastasia) were adapted into a play by French dramatist Marcelle Maurette, which toured Europe and America with Viveca Lindfors in the title role.[5]

While the play and film depict Tsarina Marie Feodorovna as privately accepting Anna's legitimacy, the actual Tsarina publicly denounced the Anderson as an imposter in 1928.[4] The Copenhagen Statement, as it would come to be known, explained: "Our sense of duty compels us to state that the story is only a fairy tale. The memory of our dear departed would be tarnished if we allowed this fantastic story to spread and gain any credence."[4]

The play and film do not reveal whether Anna is the Romanov princess, but suggests through subtle hints that she is.[3] The gradual realization of her true identity is juxtaposed against Bounine's growing romantic interest in Anna. In one speech, he says to Anna/Anastasia that he cares for who she is and not what her name is.

Production

[edit]Casting

[edit]The film marked Bergman's return to working for a Hollywood studio after several years of working in Italy with her husband, Roberto Rossellini. (Their marriage had caused a scandal, as he divorced his then current wife, Marcella DeMarchis to be with her.)

The film was also a comeback for Helen Hayes. She had suspended her career for several years due to the death of her daughter Mary, and her husband's failing health.

Filming

[edit]

Anastasia was primarily filmed on-location in Paris, with a second unit capturing location footage of Copenhagen.[3] The studio interiors were shot at MGM-British Studios at Borehamwood, England.[3] The Alexander Nevsky Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Paris, which was a center of worship for Russian aristocrats and other émigrés from St. Petersburg in the city, is featured in one of the early scenes.[6] Knebworth House was used to represent the Empress Marie’s palace.

Reception

[edit]The film received generally positive reviews from critics.[3] The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported that 93% of critics have given the film a positive review based on 15 reviews.[7] On Metacritic, the film has an average score of 61 out of 100 based on 19 reviews, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[8]

Mae Tinee of the Chicago Tribune called the film "Beautifully balanced with history and fantasy woven into a background of searing sorrow and royal pomp, this is one of the year's most enjoyable films. It is presented with wit, warmth, delicacy, and skill."[9]

Many critics emphasized the film's status as Ingrid Bergman's comeback vehicle. Jean Yothers of the Orlando Sentinel wrote "After an absence of seven years from American-made films, beauteous Ingrid Bergman returns triumphantly."[10] Moira Walsh of America wrote "Given a chance, Miss Bergman looks as lovely as ever and gives an effective high-tension performance."[11]

Some critics believed the film was bound too much to the static settings and theatrical "scenes" of the play, but additional, essentially decorative, ball scenes were added to open up the action.

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[12] | Best Actress | Ingrid Bergman | Won |

| Best Music Score of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture | Alfred Newman | Nominated | |

| British Academy Film Awards | Best Screenplay | Arthur Laurents | Nominated |

| David di Donatello Awards | Best Foreign Actress | Ingrid Bergman | Won |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama | Won | |

| Helen Hayes | Nominated | ||

| National Board of Review Awards | Top Ten Films | 8th Place | |

| Best Actor | Yul Brynner (also for The King and I and The Ten Commandments) | Won | |

| New York Film Critics Circle Awards | Best Actor | Nominated | |

| Best Actress | Ingrid Bergman | Won | |

| Photoplay Awards | Most Popular Male Star | Yul Brynner | Nominated |

Twin film

[edit]A West German film based on Anna Anderson, The Story of Anastasia (German: Anastasia, die letzte Zarentochter) was released the same year.[13] Both films star Ivan Desny. (see: twin films)

See also

[edit]- List of American films of 1956

- The Story of Anastasia

- Anastasia: The Mystery of Anna

- Anastasia (1997 film)

- Romanov impostors

References

[edit]- ^ Solomon, Aubrey. Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History (The Scarecrow Filmmakers Series). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-8108-4244-1. p250

- ^ Cohn, Lawrence (October 15, 1990). "All-Time Film Rental Champs". Variety. p. M144.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "ANASTASIA (1956)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ a b c d e King, Greg; Wilson, Penny (2011). The resurrection of the Romanovs: Anastasia, Anna Anderson, and the world's greatest royal mystery. Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-470-44498-6. OCLC 610466408.

- ^ Klier, John (1995), The quest for Anastasia: solving the mystery of the lost Romanovs, London: Smith Gryphon, ISBN 978-1-85685-085-8

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Anastasia

- ^ "Anastasia | Rotten Tomatoes". www.rottentomatoes.com. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ "Anastasia Reviews". www.metacritic.com. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ Doll, Baby (1957-01-06). "La Strada". Chicago Tribune. p. 157. Retrieved 2025-02-10.

- ^ "Anastasia*". The Orlando Sentinel. 1957-01-31. p. 19. Retrieved 2025-02-10.

- ^ America: A Catholic Review of the Week 1956-12-29: Vol 96 Iss 13. Internet Archive. America Press, Inc. 1956-12-29.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "The 29th Academy Awards | 1957". www.oscars.org. 2015-03-26. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ "The Problem of Anastasia: Two films on a single pitiful theme", The Times (February 20, 1957), p. 11

External links

[edit]- Anastasia at IMDb

- Anastasia at the TCM Movie Database

- Anastasia at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Anastasia at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1956 films

- 1956 drama films

- 20th Century Fox films

- American drama films

- 1950s English-language films

- American films based on plays

- Cultural depictions of Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia

- Films about amnesia

- Films directed by Anatole Litvak

- Films featuring a Best Actress Academy Award-winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Drama Actress Golden Globe-winning performance

- Films scored by Alfred Newman

- Films set in Copenhagen

- Films set in France

- Films set in 1928

- CinemaScope films

- Films shot at MGM-British Studios

- Films with screenplays by Arthur Laurents

- 1950s American films

- Films shot in Paris

- Films shot in Copenhagen

- Films shot in Hertfordshire